From Derick Velazquez in January to Lance Lynn in November, there were 112 ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries requiring reconstructive surgery — commonly called Tommy John Surgery (TJS) — in the 2015 season. Once a career-killer, UCL injuries have become a much more survivable injury over the last 30 years. And while more and more players are successfully returning from TJS, the procedure itself is a catastrophic event and requires a minimum of a year to recover.

That makes predicting UCL injuries a valuable and worthy endeavor. From the GM to the fantasy owner, being able to steer away from players with early warnings signs of UCL injuries can save a team’s season. The red flags for UCL injuries are not big, though, and many UCL injuries appear from nowhere. But using a large data set, culled from a variety of valuable resources, we can find the tiny red flags, the little baby red flags.

For the past seven months, I have been working with Tim Dierkes and his staff to develop a model to predict Tommy John surgery. The creation of this model required, quite literally, hundreds of thousands of lines of data and hundreds of man hours to combine and connect and test data from a variety of disparate sources. The project also took, as a sacrifice, one of my computer’s CPUs, which burned out shortly after completing some herculean computations. Fare thee well, i7.

[For further details on the process, results, and limitations of this study, please refer to Bradley’s MLBTR Podcast appearance and MLBTR Live Chat.]

The Results

The following is an attempt to quantify the risks that foreshadow potential UCL injuries. It is a combination of FanGraphs player data, Jeff Zimmerman’s DL data, PITCHf/x data, a bunch of hard work, and the keystone data: Jon Roegele’s TJS data, as stored on Zimmerman’s Heat Maps. We also checked our numbers against Baseballic.com, which houses arguably the most comprehensive injury data online.

And while most efforts at quantifying TJS risk have focused on recent appearances or recent pitches, our research takes a step further back and examines injury risks on an annual basis. It seeks to consider the problem from the GM’s view, and not the game manager’s.

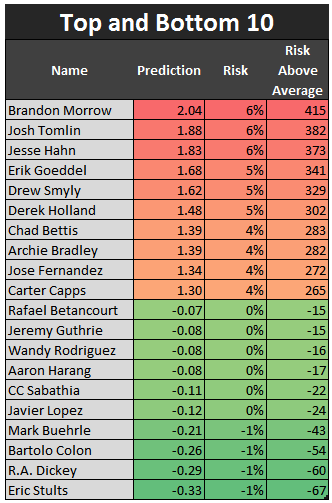

The following names are sorted by greatest risk to least. For more details about the columns and the model that has created this data, continue reading after the embedded data.

Click Here for Interactive Tableau and Full Results

The results include three terms that help define where the players fit:

- Prediction: My method of regressing the variables against pending TJS events resulted in a scale of 0 to 7, where 7 is the season before a player undergoes TJS. So our top player above, Brandon Morrow, ranks a 2.04 out of 7.00, meaning he is nowhere near a player about to absolutely have a shredded UCL. But it is certainly above average.

- Risk: This is the player’s prediction, divided by the highest possible result, 7. Then, I then multiply the result by the degree of confidence I have in the model, which is the R^2 of .22. R^2 is the statistical tool for checking how much the model explains the variation in the data. It is unconventional to multiply the regression result against the R^2, but I wanted to firmly assert that this model can only explain — at most — 22% of the variation we find in the TJS population. I have additionally listed the results as whole numbers in an effort to limit the perception of precision that a decimal place conveys.

- Risk+: This is merely a representation of how far above average or below average the player’s risk is. Here, 0% indicates a league-average risk; 100% is 2x the league average; 200% is 3x, and so on.

The Raw Numbers section includes the specific variables involved (explained in further detail in the “The Inputs” section). The Indexed Section includes the same data, but indexed (unless it is binary). That means the average is 100, twice the average is 200, and so on. This is the same as wRC+ or OPS+ or even Risk+, minus the % sign and with league average at 100 instead of 0%.

The Inputs

Over the preceding months, I have tested, prodded, and massaged many numbers. These were the factors that ultimately proved to have the strongest, most consistent relationships with impending TJS:

- LHP = 1: MLB pitching staffs have been 28% left-handed since 2010. TJS victims are 25% left-handed. Throwing the ball with your right hand — unlike Tommy John, the original — is the first tiny red flag.

- St. Dev. of Release Point: Previous studies (such as here and here) have attempted to connect release point variations with injuries. In the various models I created, release point had a consistent, while small, predictive power. I did not control for whether or not the pitcher appeared to have a deliberate difference in release points (as in, guys who pitch from multiple arm slots), but the infrequency of that trait does not seem to impact the variable.

- Days Lost to Arm/Shoulder Injury in 2015: After many different permutations of what constitutes “an injury” or an “arm,” I landed on this unusual definition of an arm/shoulder: It’s everything from the wrist back, including the elbow, shoulder, and — why not — the collarbone. So it’s basically the principle upper-body actors of the throwing motion. No fingers, no legs. So if a player injured this arm/shoulder/collarbone area, the sum of their missed days has a decently-sized red flag planted on it. This is among the most important predictive factors for TJS — which makes intuitive sense. Previous injuries could be a forewarning of a bigger injury, or it could be a contributing factor in creating an UCL injury as pitchers compensate for a tweak or a partially-recovered injury.

- Previous TJS?: This is a count of how many times the pitcher has gone under the knife. While only a small percentage of pitchers have Tommy John Surgery in their career, it strongly predicts a second surgery. Since 2010, there have been 10,000+ pitchers in the majors and minors combined. In that time, about 560 pitchers in the minors and majors have had TJS, and 57 were repeats. So the ratio of MLB and MiLB players to TJS victims is about 5%, but the repeat rate is over 10%. In other words, TJS begets more TJS.

- Hard Pitches: This variable is the sum of four-seam fastballs (FA), two-seam fastballs (FT), and sinking fastballs (SI) as categorized by the default (MLBAM) PITCHf/x algorithm. Various attempts to include different pitch types and pitch counts all proved inferior to just a raw count of the hardest three pitches that the PITCHf/x database records.

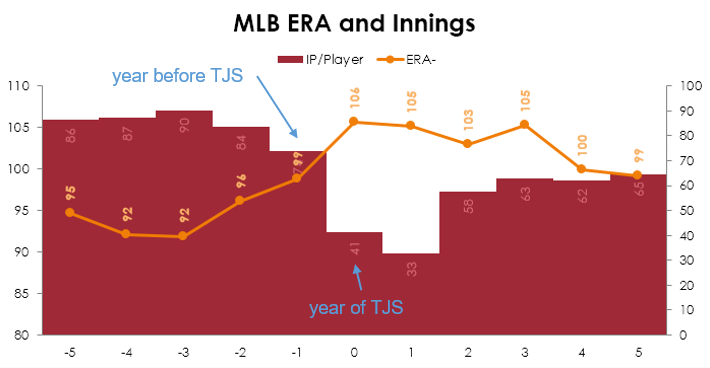

- ERA-: This is a park-, league-, and era-adjusted ERA, as reported by FanGraphs. This is the most puzzling part of the model, and the part I am least comfortable about, but a good ERA- (below 100) correlated weakly but negatively with good health. Possible bad data aside, the only theory I can muster to explain this is the idea that pitchers in the middle of good years are more likely to pitch on short rest or make emergency relief appearances in extra-inning games or key late-season games. The elite closer is more likely to pitch the three-consecutive-days marathon than the struggling middle reliever.

- Age: Here is another iffy variable. Why do older guys without a previous TJS have fewer Tommy John Surgeries? Well, for one, there are fewer older pitchers than younger pitchers, but even after we control for that, we see fewer 38-year-olds going under the knife. The reason is probably that fewer late-career guys see a major UCL tear as worth trying to overcome, and instead call it a career. Few can forget the end of Ramon Ortiz’s 2013 season, when the then-Blue Jays starter suffered what appeared to be an UCL injury and left the field in tears. Many assumed the 40-year-old righty would end his career then, but Ortiz was fortunate enough to avoid a UCL tear and managed to pitch in Mexico as recently as 2015. Had the 2014 injury been an UCL tear, Ortiz may have just ended his career then. There is also some survivor bias in here. Guys with truly durable UCLs are more likely to make it to their age-35 seasons (and beyond).

Here is a breakdown of the variable and coefficients involved:

| Coefficients | Standard Error | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.6319 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| Average of LHP? | -0.1847 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Avg Arm Slot STDDEV | 1.6667 | 0.54 | 0.00 |

| Arm/Shoulder? | 0.0110 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Previous TJS? | 0.2981 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Hard Pitches | 0.0001 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| ERA- | -0.0020 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Age | -0.0524 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

It is important to remember that the coefficients here do not visibly represent the strength of each variable because they each use a different scales. For instance, the largest Previous TJS is 2, but the largest Hard Pitches number is 2,488. (That said, Previous TJS is a much more predictive variable.)

P-values, in short, are the probabilities that the given variable is actually meaningless. Traditionalist might bristle at some of the P-values involved there. I personally find the customary cut-off P-values of .10, .05, or .01 artificial and unnecessarily limiting. Others are welcome to disagree.

Why is Player X So High/Low?

So your favorite pitcher is Brandon Morrow, and you’re distressed to see him top the charts here. Let’s look at why:

- In 2015, Morrow missed 155 days after having debris removed from his shoulder. That’s 22x the league average among pitchers that completed at least 30 innings. No other pitcher on this list missed more days. (The average time missed was a little under 7 days.)

- And despite missing most of the year, he still managed to throw a large amount of fastballs because, as Brooks Baseball puts it, he “relied primarily on his Fourseam Fastball (95mph) and Slider (88mph)…” Morrow threw his fastball almost 60% of the time in 2015.

- Lastly, he is just barely on the wrong side of the average age of this group. While the age variable is still an odd one, it is important to keep in mind that TJS culls the herd in the early years. If Morrow were 36 and coming off an injured season of this magnitude, he would still probably be the most likely TJS candidate, but he’d get a few bonus points for proving his UCL could have lasted this long in the first place.

I am pleased to see the likes of R.A. Dickey, Mark Buehrle, and Bartolo Colon at the bottom of the list. They are older pitchers with incredibly steady release points and no recent injury history (Dickey, of course, doesn’t have a UCL in the first place, though obviously the statistical algorithm in question doesn’t take such factors into consideration. We left his name in the results regardless of that fact, for those wondering why, as a means of illustrating the type of pitcher likely to rank low on the list). Of course, these guys, at their age, are perhaps even more likely to be ineffective and retire mid-season than they are to suffer a catastrophic injury, but that is neither here nor there.

Free agent Tim Lincecum also makes the list, and in a very positive way with a risk that is 51% below the league average. While any GM or fantasy owner looking into a Lincecum 2016 season will no doubt be aware of his injury history, it is a great sign for the two-time Cy Young winner hoping to move forward in his likely-post-Giants career. The strongest contributing factors to Lincecum’s risk, however, are his inconsistent release point and the fact he makes a living off mixing up four generally slower pitches. While he has not shown great effectiveness in the past four seasons, avoiding TJS could buy him enough time to find a rhythm with his greatly decreased velocity.

Young Marlins ace Jose Fernandez only missed 35 days due to a biceps issue — if we don’t count the 97 days he missed recovering from TJS in 2015 — but that previous elbow operation combined with his young age suggests he is at greater risk of a second TJS heading into 2016. Again, we need a caveat here to remind us that age, while a predictor of TJS, may not be a good predictor of UCL tears.

Mark Buehrle, Bartolo Colon, and Eric Stults all have negative risk rates. Does that mean they are growing additional ulnar collateral ligaments? Yes. Almost certainly.

Rejected Variables

There are a few variables not included that might seem intuitive or necessary to include, but ultimately did not make the cut:

- Velocities: Early versions of this model included pitch velocities, but it became apparent after later revisions that pitch velocities — at least given the present variables — was serving as a poor proxy for the number of hard pitches thrown. It follows that guys with fast fastballs throw those fastballs frequently. Take, for instance, freshly Rockie’d reliever Jake McGee, who has a scintillating fastball and rumors of maybe another pitch. Throwing hard may not actually lead to elbow injuries, but throwing a LOT of hard pitches might.

- Other Pitch Frequencies: Throwing breaking stuff did not seem to have a meaningful relationship with TJS events — at least above and beyond the relationship with hard pitch totals. That does not mean sliders might not result in shoulder injuries or knuckleballers don’t have more fingernail issues, but in the given sample, with the given scope of our investigation, breaking and off-speed pitches did not create meaningful relationships.

- Altitude of Home Park: Despite the considerable effort it took to match up each player’s home park with their park’s altitude, this attribute appears to have no effect on TJS. One might suspect that environmental issues impact the prevalence of certain injuries, but we can cross off altitude for now.

- Non-Arm Injuries: I figured leg injuries — given how important legs are in delivering a pitch — or general injuries might have a connection to TJS if in no other way than causing inconsistency in the pitcher’s delivery or release. But once we add in the arm/shoulder injury days into the calculation — along with previous TJ operations — the value of other injuries goes away.

- Injuries in Previous Seasons: Despite connecting players up with five years of injury history, the unstable relationships (i.e. high P-values) also came with negative coefficient — suggesting an injury in 2013 makes you stronger against a possible UCL injury in 2015. That makes no sense.

Room for Improvement

Without comprehensive dumps from the PITCHf/x data at Brooks Baseball or the Baseballic.com injury database, and without good information on late-career UCL injuries that result in retirement instead of TJS, and without medical records from these players themselves, we will always be playing catch-up with our prediction models. If I am a team considering one of the players listed above, I would defer to medical and pitching experts opinions following a thorough medical examination.

But from our perspective, from the data available in the public sphere, these are the best, strongest tiny red flags I could find. And I hope and expect they will push this field forward. If you’d like to discuss my Tommy John research further, check back at MLBTR at 7:30pm central time, as I’ll be doing a live chat.

A special thanks to Jon Proulx who helped do some very boring data work with me!

R.A. Dickey does not have a Ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and therefore cannot have Tommy John.

Nice catch. Kind of a one-off though, this model is saying he’d be among the lowest risk even if he did have a UCL. Bradley didn’t build in a “does he have a UCL” variable or anything.

Haha! I didn’t even think about that!

Well, I still stand by my research, and I may catch some heat for this, but I am officially predicting R.A. Dickey will not have a major UCL injury this year.

And you’re right – I guess that means the predictability model is fairly sound!!!

This is great work, kudos. I’m curious if your research led you to see a sudden velo spike as a red flag right before TJ? I recall Keith Law calling that with Danny Duffy a couple years back. Thanks.

I attempted to answer this very statement here: hardballtimes.com/velocitys-relationship-with-pitc…

Oh man, bang on. Thanks, i really enjoyed your work.

In all fairness, the editing staff added that after his comment.

He does mention that in this arrival, but he said he included him anyway

look right above you – that was added to the article later, because of these comments

Glad to see Dickey has negative risk given that he lacks a UCL to repair.

Great article, but considering that R.A. Dickey doesn’t even have a UCL in his pitching arm, he should probably be last on the list.

Wow, what a post!

Agreed – Excellent work Dr. Woodrum! Please continue producing original informative research like this article. Again, great job.

Awesome stuff! Ill have it more in-depth after work. I like the dummy variable for LHP, but what about on for height? More specifically looking at either smaller or larger pitchers?

This is something that hits close to home for me, I actually did my Econ Sr. Thesis on this exact issue 🙂

Height was a real iffy variable for me (I actually meant to include it in the writeup, but forgot). It missed the cut by a single model version. I suspect there is a role height plays into it, but I wonder if height is also just impacting velocity, which impacts Hard Pitch usage. When I incorporated Hard Pitches, height became effectively useless — though I can’t say there’s a direct causation there.

Thanks for the response! And yeah I could definitely see that. Itd be interesting (at least for me anyway) to see if the hard throwing short guys actually do have that elevated risk that they seem to be perceived with. Again, great work and an tremendous read!

Joining the chorus of “excellent posts” but as a former college pitcher who is 6’8″ I’d have to imagine that height also directly impacts UCL length in the arm. Perhaps to be more precise, a metric for forearm/upper arm length may be somewhat predictive? A bigger guy may actually put less stress on the ligament as there’s more of it to absorb the strain.

Could you go back and see what the effect was of the mound height and its change?

It does my heart good to see Jake arrieta so low

Me too. I own him in a fantasy keeper league. But even though his risk for a severe UCL injury may be low, my guess is that he’s still at high risk for some type of shoulder or arm injury—that slutter he throws is supposed to be hard on the shoulder. And he throws it a lot.

The bummer for me is Smyly. I own him in a deep league and was planning to keep him. To play it safe, maybe I should drop Smyly and keep Gio Gonzalez, even if his skills appear to be declining.

About the only thing I really learned was that if you’re approaching forty good chance you’ll grown another ligament in the throwing elbow. Where’s mine?

What list did you read? Archie Bradly, Jose Fernandez and Drew Smiley are all under 28 and listed has high risk and those are just the pitchers I know off the top of my head.

And I ask you, What comment are you responding to?

Yours. I don’t see how you take from this article that it’s saying pitchers over 40 are high risk for tjs. If you were reading this article, you would see both older and younger pitchers are on both sides of the risk factor

That wasn’t, in any way, his comment. He quipped – as Bradley did – that pitchers over the age of 40 naturally GROW extra UCLs, thereby avoiding serious injuries.

Little question how can Dickey have no UCL and still pitch? I know he’s a knuckleballer buy still he throws a fastball on an off chance

This is fantastic work. I’ve been waiting for someone to expand on the “Verducci effect.” I saw one tremendous flaw in your analysis. Before you dismiss me, let me point out that I am a baseball coach, blogger and former pitcher. The most important tell tale sign of a coming elbow injury is bad mechanics. I watch for pitchers who put too much stress on their arms. I teach young pitchers that you get your power from your legs and your upper back – not your arm. I have them watch video of Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, Mariano Rivera, etc. A fluid windup, a repeated delivery, a powerful drive toward homeplate, followed by a gentle, not violent whip of the arm. Guys who come across their bodies always blow out their elbows. I predicted future surgeries for Kevin Brown, Jake Peavy, Stephen Strasburg and Zack Wheeler (more because of the obvious inverted W in his case. Masahiro Tanaka has a similar issue). I’m not suggesting good mechanics alone can protect a pitcher from elbow injury, but bad mechanics put undue strain on the elbow and, I believe are the number one red flag for future TJ surgery. I’m no Frank Job and I am not an MLB coach, but I think I know what I’m talking about. I plan to make this the focus of my Friday blog post on mets360.com as I’m tired of reading about how Noah Syndergaard is next in line just because he throws hard and his innings increased.

mattymets – How would you objectively define “bad mechanics”? I think Dr. Woodrum has tried to take this factor into account with variables like Release Point, Arm Slot, and Arm/Shoulder Index.

Addyo4552 – my point is that not every single aspect of baseball is quantifiable. That’s why, with all the algorithms and all the data, teams still hire scouts.

You hit the nail on the head. Inverted L, shoulder hyperabduction, timing issues, throwing too many sliders and curveballs and other mechanics related issues are thew biggest risk factor for arm injury. I watched this closely for years a few years ago and saw without exception that guys who were coming down with major arm injuries had huge mechanical problems particularly arm action. At footstrike, the arm should be up and in the ready position, but for many, the arm is not up and has to hurry to catch up resulting in tremendous forces being applied to the UCL. It is similar to throwing your car in reverse, flooring it and then throwing it into drive and flooring it without touching the brake pedal. That’s what guys are doing to their arms with every pitch who throw like this. Obviously, the harder you throw with these kinds of mechanics, the worse the effect is especially if you are an arm thrower. Mark Prior, Anthony Reyes, Shaun Marcum, BJ Ryan, Chris Carpenter, Yu Darvish among many others. It is a huge contributing factor. Prior had absolutely terrible arm action and BJ Ryan had the worst inverted L I’ve ever seen; both are out of baseball. Both Ryan and Marcum were also arm throwers with very short strides. This anaylsis completely misses these factors which unfortunately makes it flawed.

It is not flawed because it doesn’t pretend to account for everything. There is a note above about the statistics R^2 (R squared), which quantifies how much of the dependent variable (TJ surgery) the independent variables (all the factors that went into the model) can explain. R^2 for his model is .22. This means that only 22% of TJ surgeries are predicted by this model. So it is not appropriately to call the model flawed because it doesn’t taken into account every variable that you think is important. It just means that predicting TJ surgery involves lots and lots of factors, and his model has successfully determined 22% of them. Future versions of the model may add other variables in, like the ones you try to identify, which could raise R^2 as a consequence.

Please forgive my terrible spelling and grammar above. Apparently the edit button has vaporized.

Biomechanist here. mattymets: pitching mechanics are quantifiable, via 3-D motion analysis. Things like joint sequencing, valgus torque about the elbow, and shoulder and elbow angles at release are generally evaluated by sports scientists within baseball. Though the technology isn’t available to do it yet on a pitch-to-pitch basis in a game, many teams do use this technology in their preseason or offseason as a means of evaluating their pitchers. However, to adyo4552’s point, the difficult part is in identifying ‘good’ from ‘bad’ in a meaningful and objective way. Biomechanics can identify differences between players and populations, but in order to identify something as being bad, you need to match it up with injury or performance in the long term. Coaches certainly have notions of what constitutes ‘good’ (remember when Mark Pryor was considered God’ gift to pitching mechanics?), but usually those determinations are made independent of rigorous scientific study. The only way that they will become a part of predictive models of injury is for more of those data to become available to the public, which most teams and players (AND AGENTS!) have a vested interest against.

I would think that the only way to quantify what is good mechanics vs bad would be to have a pain score. If someone is throwing without pain, then it’s gets pretty hard to say what is good vs bad. Also, what about high stress innings (higher than average pitch counts in an inning) vs just looking at hard pitches?

Not good news for the Yankees – Eovaldi, Tanaka, Severino, and Pineda are all at least 60% above average for future TJ.

Fascinating read. One of very few published predictive models of injury I have seen for professional sports. You did a fantastic job both explaining the model in laymen’s terms and describing the inherent limitations of this type of research. In my opinion, too many ‘experts’ are stuck looking for a single scapegoat for catastrophic injuries in throwing athletes–whether it be poor strength and conditioning programming, pitches/innings, or ill-informed pitching coaches. As the paradigm continues to shift towards data-informed decision-making, I’m excited to see work like this become more a part of the discourse about players and organizations moving forward. Well done.

I enjoyed your post. If there was anyway to add to your statistical analysis the amount of innings young pitchers ages 8-18 are throwing playing travel ball in the USA then your program would really have added validity. TJ surgery is a epidemic in our youth programs of today where pre-teens and teenagers alike are playing over 60-100 games a year. The damage being done may not show results of damage to their ligament until they have signed a professional contract but believe me, damage is being done. I also believe lefthanded pitchers may be more susceptible to the ailment because a higher percentage of those LHP’s throw across their body. Mechanics play a big part in players having shoulder and elbow issues.

As a Giants fan I’ve noticed the team doesn’t get TJs and if you look at all Giants starters they are all among the lowest risk. Hmm… Does the team know something others don’t?

Before more people complain of Dickey being in here with no UCL, read the whole thing first ” (Dickey, of course, doesn’t have a UCL in the first place, though obviously the statistical algorithm in question doesn’t take such factors into consideration. We left his name in the results regardless of that fact, for those wondering why, as a means of illustrating the type of pitcher likely to rank low on the list)”

they added that later because of the comments

Thanks for the info! I didn’t know that

What a load of garbage- is there nothing better to occupy ones time. Completely useless and BS

Completely agree.

wait, how is Rafael Betancourt so low considering he sat out most of 2015 with an elbow injury and had TJS as recently as 2013. This seems like a weird result.

The only variable factor that should carry less weight in the risk analysis is “Days Lost to Due Injury”. The reasons and number of days players are on the DL are not always what they seem. That said, the other factors such as ERA, hard pitches, etc. are real, verifiable numbers. I like the approach though……very well thought out. Another variable to consider would be “Number of stressful innings (more than say 20 pitches in an inning)”…this can really tax a pitchers arm especially if its late in the season and he is already feeling the effects of 12-15 games. …and pitching density where you evaluate the number of pitches thrown is a certain period of time……..

Yeah, I also found the zero mentions of stressful pitches to be weird as that is the factor that has been most talked about in relation to pitcher health/durability over the past year.

I’m guessing it’s just another thing that the author forgot to include in the writeup because he found it unpredictive rather than it being something that he just neglected to look at. It would be good to know for sure though.

Awesome study. What kind of regression was used? Logistic?

This was a very ambitious study. Very fascinating!

Why didnt you include a starter/reliever variable?

Also I’ve always thought that having a pitcher starting games and turning him in to a relief pitcher, back and forth, could have negative impact on the pitchers arm.

Is the LHP thing worded wrong or do I just not understand it? If they only make up 28 percent of pitchers but 25 percent of TJS wouldn’t that make them more susceptible?

I get what you’re saying, I had to re-read it myself after you mentioned it. But he does have it worded correctly.

If 28% of pitchers are left handed, then for then to be equally susceptible to the surgery as RHP, 28% would be the number that has them equally susceptible. Since the number is 25% instead, they are less susceptible than a RHP.

I was wondering whether or not we’d see DIckey on this list. I didn’t find it as funny that he made the list itself, so much as there is one person ahead (behind?) of him. I find it much more impressive that a single person has less of a chance of tearing their UCL than a guy who doesn’t actually have one.

That would make them less susceptible. They are a lower percentage of TJS than they are of the general pitcher population. They are 11 percent less likely to have TJS than right handers.

You could say that Lefties are 10 percent of the general population but 25 percent of TJS. That would make them more susceptible than the general population. However, this only really means that Lefties are 280 percent more likely to be in MLB than the general population.

I’m pretty sure that is incorrect I’m no math expert but the only way what you are saying would make sense is if the total number of TJS is the same as the total number of pitchers in baseball and I’m pretty sure not every pitcher in the league has had a TJS, making up a little over a 1/4 of the league but being responsible for 1/4 of all TJS would seem to say they are more likely to get TJS.

Look at it as Pies 28 percent of all pitchers in baseball is going to be a smaller slice of pie than 25 percent of all TJS surgeries in baseball.

I realize that is the wrong way to look at it as a pie will be divided the same no matter what but what I am getting at is the total number of pitchers in baseball is a much larger number than the total number of TJS, You are looking at 28 percent of total pitcher population vs 25 percent of TJS the fractions would be much different.

Say we have 1000 total pitchers 280 are left handed, we have 100 TJS 25 percent are left handed

25/280 LHP with TJS vs 75/720 RHP with TJS 11 percent of this LHP population had TJS vs 9 percent of the RHP

I don’t know the actual numbers and these are way off but this is how they should have got the correct percent

I’d like to see this addressed by the author.

Massively good work!

One question: My understanding is that at least anecdotally the overhand curve is one of the hardest on the shoulder over time, which seems to make sense when you consider the mechanics of the pitch. Were you able to track those kinds of injuries?

Beautiful work. I’d be interested in seeing it sorted by initial farm system.

Great job, guys. It’s a good starting point for hopefully what turns out to be a way to prevent these injuries.

Why doesn’t Adam Wainright appear in the full list?

This is the biggest bunch of crap I have ever read. Couldn’t get past the first two paragraphs. There is absolutely zero way to quantify whether a player is going to need TJ surgery.

You mathletes can come up with all kinds of formulas but you’re never going to predict how a player is going to perform in a particular year or whether they will or will not be injured.

Same as sabermetrics. It’s nothing more than a guess. You might be able to talk in fancy mathematical terms but your guess is as good as the next guy’s. What a waste of space on this site. Get a grip.

“This is the biggest bunch of crap I have ever read!”

One sentence later…

“I didn’t even read 95% of it!”

I dare say, this could be the greatest comment in the history of MLBTR.

I didn’t read the entire article because the premise of predicting player performance and injury using math is laughable. The author even stated that only 5% of 10,000 professional pitchers needed UCL repair in the past 5 years. Not exactly a pct that screams, ” epidemic”.

If you belief tripe like this is going to ever drop the percentage of arm injuries to zero, you’re as sad as this article. Just because sabermetrics/mathematical analysis has crept into the game – unfortunately- doesn’t mean it is valid.

Arrogant, childish, and rude.

It’s one thing to read an article and disagree with it’s premise. It’s another to admit you haven’t read it, call it crap, and write off the premise altogether because you think you’re always right.

And if it’s crap and you can’t believe the premise, hit the back button on your internet and move along. No need to be rude.

The human elbow/shoulder is not designed to throw thousands of pitches at max, or close to max effort, for years on end without suffering wear and tear and/or injuries. Any one that has ever pitched competitively knows that.

I never had any real problems with my elbow until I started throwing the slider. Throwing the fastball and curve are relatively easy on the shoulder/elbow. It’s the stress of the slider and splitter that wreak havoc on the slider. Just my opinion.

Anecdotally, I have noticed a lot of pitchers that throw hard sliders and splitters damaging their UCL. From my own experience, I can see why. No one can ever be sure of having the ” proper mechanics” to avoid injury. If I recall, most scouts raved about the ” perfect ” mechanics of Mark Prior and Steve Avery and those two were affected by arm injuries that shortened their careers. You just never know.

*insert Morgan Freeman, ‘he’s right you know’, meme*

Wow, just ground-breaking stuff. Truly impressed with this…regardless of it’s eventual accuracy, takes real hard work and courage to publish this.

RA Dickey doesn’t have an UCL. Therefore, he can’t tear it

Having torn my UCL completely back in my playing days I would have to say that I think you missed on a couple of variables. I strongly believe I tore mine during routine warm ups the day after a game I pitched in. In that game my fastball didn’t seem to have much sink to it and it was getting hit hard. So, I wound up throwing twice as many sliders as I normally did. I firmly believe that using incorrect wrist action while throwing breaking pitches has a serious effect on the UCL. Your article was a great read and should be required reading for all hard throwing high school players. More information like this should be made available to the young players so they can work on getting their mechanics set to help avoid TJS when they get into college or pro ball.

Is there a point in a pitcher’s career after he reaches a certain age and has thrown a certain number of innings that he’s much less likely to ever have TJS, meaning the risk drops to near zero no mater how many innings he’s thrown? Just as some elbows are going to blow out early, others may never blow out due to genetics.

The fact that you smoked an I7 chip is impressive enough. In looking at Drew Smyly, I’m still wondering how you translate shoulder issues into elbow surgery? I briefly read the part about release points, hard pitches etc. but how a specific injury affects a certain part of the body based on his history? Plus with hard pitches, Smyly compared to the rest of the league is a soft tosser when you compare fastball speed. Wasn’t there some data prepared before that showed as pitchers have progressed and more and more pitchers can chuck the ball past 95 MPH that more arm injuries travel with it?

I applaud your work. I think if the majority fans realized how much data baseball teams are now generating to develop just the slightest advantage while all the while managing it back to $$$ – jaws would drop. This explosion of data has changed this game not only from a player perspective but from a FO perspective.

Thanks to all for the work put into this!

Been working on this for seven months, huh?

The uptick in UCL injuries likely has to do with pitchers nowadays throwing everything at max effort. It doesn’t matter if it’s the first inning, the 7th inning, a fastball, a curveball or anywhere in between, pitchers are taught to throw everything as hard as they can. Pitchers of the past actually PITCHED, and left something in the tank for when they needed to “reach back” for a little extra. Today there is no extra…there is max effort, 100% of the time, which puts that strain on an elbow/arm, so pretty much every pitcher is at equal risk. Matt Harvey came up with “perfect mechanics” and that worked out great.

one solution would be just go ahead and put all pitchers under the knife at a given age and do the surgery and give them a bionic arm insert.

It should be noted that I am relatively certain that R.A. Dickey does not have a UCL to replace. It was discovered earlier in his career that he actually didn’t have one.

I should have read all the comments first. I guess that was already noted.

Purely speculative at this point, but just announced Carte Capps going for an MRI and the Marlins already in the market for relievers. Carter Capps is in the Top 10 of this list.

Aaaand, down goes Capps… TJ surgery confirmed for CC… Curious to see how many more of the top 10 fall victim this season (while quietly hoping it’s zero… ESPECIALLY hoping #3 on the list can stay healthy)

From a fantasy perspective, Hahn and Holland scare me the most

In the very first sentence, you mention the number 112 surgeries. At what level??? Pros only? Including little league? Please specify as it sets up the whole article, like an attention-getter should.

I was gonna just laugh this off, but wow…lol, this guy^

While this is a very in-depth and risky piece you can only go so far. Lest we forget, Its a website that while often wanders off to affiliated MLB topics, its still about MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL.. you really expect them to crunch the numbers of every baseball player in the nation, young and old? Should we include my four-year-old tee-baller? Their research has boundaries for a reason.

Tired of you internet trolls (and yeah I’m looking at you) who are jealous of someone else’s courage and innovation, too afraid to give credit where credit is due. This has been a serious hot topic and few pundits have even has the audacity to weigh in, so instead of spitting on it with some silly expectation, be realistic and find another hobby other than spreading negativity. Or split hairs for the rest of your life and keep up the envy, green is your color.

Hi, I’m new to this site number one, and so I really have NO idea what exactly gets posted here. Especially with a name like “Trade Rumors.” Does that mean only trade rumors? I guess not. So thanks for setting me straight on that (I guess). I’m not even sure how your reply really relates to my question. What about it is negative? Because I want more info? And how do I know whether it’s MLB only, don’t you think 112 in one year is an awfully high number? I mean like not remotely believable? Hopefully the author will clarify this point. BTW, just because I have a question doesn’t mean I am not appreciative of the article.—And I am not a troll. I don’t even live under a bridge. You might want to look at your own negative tone too.

I wonder if average % of top FB velocity (or differential between average FB velo and top FB velo) would have an impact. That is, do guys who consistently throw closer to the top of their FB velo range have a higher rate of TJS?

For example,

If Pitcher A has a FB that tops out at 98 mph and his average FB sits at 96.5 mph, is he more likely to have TJS than Pitcher B who also has a FB that tops out at 98 mph, but whose average FB sits at 95.5 mph?