Overview

Teams must consider two thresholds when promoting a top prospect. A player is eligible for an extra arbitration season as a Super Two player if he has between 2.086 and three years of service time and he ranks in the top 22 percent in service time among players with between two and three years. The 22 percent clause means that the Super Two threshold is a moving target, but teams can usually feel safe about promoting a player in early to mid-June with the idea that he won’t be a Super Two player three offseasons later. A Super Two player can be eligible for arbitration four times rather than three, which means that a Super Two star player can make millions more in his arbitration seasons than a similar player who does not have that designation.

Teams must also consider a player’s free agency threshold. A player becomes eligible for free agency after six full years of service time, which means teams must consider a separate date in mid-April before which a player can become a free agent a year early.

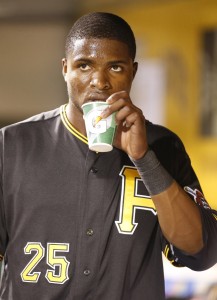

We’ll leave aside, for now, the question of whether it’s wise for teams to delay promotion of top prospects in order to avoid Super Two status or free agency, and simply observe that the current system provides them at least some incentive to do so. The Pirates promoted Polanco on June 11, after months of criticism from analysts and fans who watched Polanco post great numbers at Triple-A while Jose Tabata and Travis Snider struggled in right field for the Pirates. (Josh Harrison handled the position for about a month before Polanco arrived and played much better.) Major League Baseball received some criticism, too, for creating the rules that made the Pirates’ decision rational (or arguably rational. Few commentators offered viable alternatives to the Super Two system, however, with Baseball Prospectus’ R.J. Anderson (subscription-only) being among the few to make a strong attempt.

If the Pirates held Polanco in the minors for two months longer than they would have without the Super Two system in place, that’s not nearly the tragedy many fans and commentators made it out to be. ESPN’s Dan Szymborski, the creator of the ZiPS projection system, tells MLBTR that based on information available in mid-April, promoting Polanco on June 10 rather than April 15 projected to cost the Pirates about one win. (And the Pirates might well have waited to promote Polanco even without the Super Two rule, given their longstanding record of allowing players time to develop in Triple-A before promoting them.) That’s unfortunate for the Pirates and their fans, but it’s hardly a travesty. A few cases like Polanco’s each year likely do not justify sweeping changes to the existing system.

Many large-scale rules involve thresholds that can be less than ideal on the micro level while producing good results on the macro level. For example, it isn’t ideal, or fair, for an irresponsible 16-year-old to be legally allowed to drive (if he or she can pass a driving test), while a responsible 15-year-old with excellent hand-eye coordination cannot. But the 15-year-old will soon be 16, and so that unfairness will soon be rectified. Meanwhile, the existence of a threshold that permits small-scale unfairness keeps the rules simple and helps prevent charges of arbitrariness.

Preventing teams from manipulating players’ service time is not a simple matter. As long as arbitration eligibility and/or free agency eligibility are tied to service time, and as long as teams control when their players’ service time clocks begin, teams will be able to use players’ promotion dates to manipulate their salaries and/or years of control.

So, for example, even if MLB were to eliminate the Super Two designation while maintaining current rules regarding free agency eligibility, teams could delay the promotion of top prospects who appeared to be ready in August or September and wait instead to promote them in mid-April. We would see fewer mid-June promotions for top prospects, but we would also see fewer mid-August promotions and more mid-April promotions, and the criticism of MLB’s rules would simply take place in August and September rather than April or May. If the goal is to prevent teams from delaying the promotion of top prospects who appear to be ready, simply changing the thresholds of arbitration or free agency eligibility will not work.

Untethering Free Agency, Arbitration Eligibility From Service Time

One solution to eliminate thresholds that can prevent teams from promoting players when they’re ready might be to untether free agency eligibility and arbitration eligibility from MLB service time. If a team were not worried about the number of years it could control a player, or about his salary during his arbitration seasons, it would be free to promote him whenever it deemed him ready.

This would, however, be a radical change with far-reaching consequences. With enormous payroll disparities between teams, MLB depends heavily on young players’ cost-controlled salaries to maintain competitive balance. Without cost control, it would be nearly impossible for smaller-payroll teams like the Athletics, Rays and Pirates to compete. The current rules regarding free agency and arbitration eligibility are the mechanism that allows player salaries to remain cost controlled. So if MLB and the players’ union were to agree to untether free agency and arbitration eligibility from service time, they would need some other mechanism to allow cost control.

One possibility would be to base free agency and arbitration eligibility not on service time, but on when a player was drafted or signed as an amateur, similar to the way Rule 5 Draft eligibility is determined. A player’s eligibility for the Rule 5 Draft in a given year depends upon his age on the June 5 before he signs and the number of Rule 5 Drafts that have passed since then. A similar system could be devised to determine free agency and arbitration eligibility. For example, a player under 19 by the June 5 before he signs might become eligible for arbitration after nine full years and eligible for free agency after 12 full years. A player who is at least 19 by the June 5 before he signs might become arbitration-eligible after eight full years and eligible for free agency after 11 years. (Players posted from Japan would continue to be exempt from these rules.) This system would enable the Pirates, for example, to promote Polanco whenever they deemed him ready, without concern for arbitration or free agency timelines.

Unfortunately, this rule would produce plenty of unintended consequences, and the cure would likely be worse than the disease. This system would be tremendously unfair to players who move quickly through the minors.

For example, the Expos drafted Chad Cordero in 2003 with the idea that he could make it to the big leagues quickly. He did exactly that and was a successful closer for several years before succumbing to injury. Because he was eligible for arbitration after his third full season, he was able to make over $11MM in his career, a total that seems reasonable, given the quality of his pitching. Under a system that connected arbitration eligibility to signing date rather than service time, he likely would have made only about a third that much, since he would have been close to the MLB minimum for his entire career. Meanwhile, a player who struggled in the minors and arrived in the big leagues after many years in Triple-A might become arbitration eligible after just one or two years. Also, such a system would dramatically limit the long-term earning capabilities of top players like Mike Trout who reach the Majors at young ages.

Allowing Neutral Parties To Determine Readiness

Another possibility might be to maintain the basic outline of the current arbitration and free agency timelines but to allow arbitrators to determine when those timelines might begin. So, for example, an arbitrator might have ruled that Polanco was ready May 1, forcing the Pirates to begin his big-league service clock then even if they did not promote him. Clearly, though, this is perverse and heavy-handed, putting the determination of the player’s readiness in the hands of an outside party who would have had far less information about the player’s development than his team did. Such a system would surely also create even more complaints of unfairness than the current one.

The problem here, of course, is the existence of thresholds. When there are thresholds that determine how long a team controls a player and how much they’ll have to pay him, there will be incentives to manipulate those thresholds. One of those thresholds, the one that determines free agency eligibility, probably isn’t going anywhere, since it helps prevent star players from becoming free agents while seasons are in progress. (That is, there could be a system in which a player who is promoted for the first time in August also could become a free agent in August six years later. But that would be chaotic, and the current threshold of six-plus years before free agency eligibility helps prevent that.)

The free agency threshold is probably here to stay, and as long as there’s a threshold, there will be occasional cases like Polanco’s where teams delay promotions of top prospects even when they’re dominating at Triple-A. It’s unfair on the small scale, but reasonable on the larger scale, and that might be as much as MLB can do.

Eliminating The Super Two, Redistributing Super Two Salaries

There are, however, some more modest reforms that MLB might consider to change the Super Two threshold, leaving teams with only one threshold to consider, rather than two. One possibility might be to eliminate the Super Two completely, as Pirates president Frank Coonelly recently suggested in an interview with USA Today’s Bob Nightengale.

The players’ union would, of course, be reluctant to make such a change, given that the existence of Super Two status means more money for them. But MLBTR’s Tim Dierkes suggests that MLB could, instead, calculate the approximate percentage of overall player income Super Two status typically produces and redistribute it as a modest, across-the-board raise for players making the MLB minimum salary. (Dierkes points out, however, that it’s possible the union would still dislike the idea, given that Super Two arbitration salaries for players like David Price help set arbitration salaries for other players.)

Prorating First Year Arbitration Salaries

MLBTR’s Jeff Todd suggests making all players with between two and three years of service time Super Two players, but prorating their first year of arbitration salary based on their service time. So a player with two years and 50 days of service time would receive an arbitration-year salary prorated for those 50 days of MLB service (combined with an MLB minimum salary prorated for the rest of the year), whereas a player with two years and 100 days would receive an arbitration-year salary prorated for 100 days. Players with three or more years of service time would then go through arbitration as they do now.

Either of the last two proposals would effectively eliminate the Super Two threshold. The free agent threshold probably can’t be eliminated, and its existence should continue to provide teams with incentive to manipulate players’ service time. But at least there would only be one threshold, rather than two. Also, either proposal to change the Super Two would eliminate the uncertainty involved in Super Two status, given that there’s currently no way for teams interested in promoting a player to know where exactly the Super Two threshold will fall two and a half years later.

Photo courtesy of USA Today Sports Images.