At base, the qualifying offer system provides a mechanism that allows teams to allocate resources elsewhere while still obtaining the services of certain desirable, established ballplayers. Those players, in turn, sacrifice a portion of the contractual guarantees they would otherwise obtain in an unqualified market. In effect, the system taxes the prospective earnings of certain players who are (or soon will be) free agents.

For more background on the function of the qualifying offer system, see Avoiding The Qualifying Offer, by MLBTR's Tim Dierkes.

The impact of the qualifying offer system has come under much scrutiny over its first two offseasons of implementation. Some have argued that it unfairly penalizes the above-average but non-superstar players that are made a QO (which, if declined, requires another club signing that player to give up its best non-protected draft pick and the accompanying bonus pool money). Others claim that it allows such players a fair chance to sign a substantial contract, pointing to the offer's value (last year, $13.3MM; this year, $14.1MM). A range of arguments also claims that the system perversely favors larger-market clubs.

But before considering such criticisms (and potential reformulations of the system), it is worthwhile to put the system in its broader context, and to consider carefully how it serves (or disserves) its various actual or potential purposes. While it seems exceedingly unlikely that changes will be made before the current CBA is expired and replaced in December of 2016, the topic deserves consideration and debate leading up to that point. In approaching the issue, it is worth looking carefully at both the money at play and where the various risks, benefits, and incentives fall.

A. Overall Market Impact

How much money — in both real and baseball terms — is at stake here? Dave Cameron of Fangraphs posited recently that a 3x valuation of a draft pick's slot value is a good approximation for that pick's value. In other words, a team considering gaining or losing a draft choice would factor that amount in when assessing the potential impact of signing a player (or allowing that player to sign elsewhere). For the 2013 amateur draft, slot values rose by 8.2%, according to Jim Callis of Baseball America. I will assume both a 3x slot value in reaching a market rate, as well as a like 8.2% increase for the upcoming 2014 draft. (Note: because slots shift with every move impacting the draft, the resulting numbers will not be perfectly precise, but should nevertheless easily qualify as accurate for our purposes.)

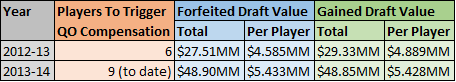

In 2012-13, six players declined qualifying offers and changed teams. According to River Ave. Blues, teams sacrificed the 17th, 22nd, 28th, 29th, 42nd, and 70th picks, while other clubs picked up the 28th through 33rd selections.

In 2013-14, to date, nine players have declined qualifying offers and changed teams. (Two QO-declining players have yet to sign.) Again, according to River Ave. Blues, teams have sacrificed the 17th, 18th, 21st, 26th, 44th, 48th, and 54th choices, while other teams gained the 28th through 34th pick. In addition, the Yankees both earned and sacrificed two supplemental first round choices. Because they finished with the worst record among clubs to have earned a supplemental pick, they would have stood to gain the first two of those picks.

Add up the slot values, and apply the 3x multiplier, and these are the results: In 2012-13, teams sacrificed a total value of $27.51MM ($4.585MM per player) and gained $29.33MM ($4.889MM per player). In 2013-14, to date, teams have sacrified a total value of $48.90MM ($5.433MM per player) and gained $48.85MM ($5.428MM per player). The 8.2% assumed increase in draft slot bonuses fairly well accounts for the rise in per-player figures, with the increase in overall impact coming otherwise from the increased use of qualifying offers.

It is worth putting these numbers up against the overall free agent spend to gauge their magnitude. I recently broke down free agent spending trends, including numbers for the 2012-13 period and the 2013-14 period to date. In the 2012-13 free agent period, clubs committed just over $1.463B in total via free agency, while this year's spending has now topped $2B (it was at $1.88B as of that post). Thus, the net draft value transferred through the qualifying offer system has been around 2% to 2.5% of the total open-market spend over the last two years.

That, surely, is a relatively minimal savings for MLB teams on the whole. When considering the full gamut of ways in which teams invest money into players — including free agency, extensions, the draft, and international signings — the money saved (i.e., allowed to be re-allocated) makes up a meager portion of the aggregate. Of course, it is worth wondering the extent to which the prospect of a future qualifying offer also transfers savings and leverage to teams negotiating extensions with players close to hitting free agency. This is impossible to calculate, but nevertheless does also transfer value to individual teams and savings to the league as a whole, as against current MLB players.

B. Impact On Individual Teams

On an individualized basis, teams assessing whether to make a qualifying offer, or whether to sign a player bound by draft compensation, have ample flexibility to value the choices at stake and decide whether and how to factor them into their decision.

Generally, a team making a qualifying offer to a player obviously reaps a substantial, albeit variable, benefit (in addition to having the right to choose whether or not to make the offer). It may ultimately retain that player at a one-year rate which, in theory, is at or below that player's market value. Or, it may instead receive a supplemental draft choice that lands between the first and second rounds of the draft. (It has been suggested that a team can sign a player that declined a QO at a lower rate than can other clubs, but that is not entirely true: once the offer has been declined, a re-signing effectively entails the sacrifice of a draft choice that, as explained below, comes with roughly the same value as the choices given up by other teams.)

A team signing a player that declined a qualifying offer, on the other hand, theoretically ends up in a neutral position, because it can discount its offer by the value it places on the pick that it sacrifices. While draft picks move as they are added and subtracted, teams have a very clear idea of what they are giving up in future value, and can apply their own valuations (including the tradeoff of present and future, and the actual slate of available draftees) to reach a discount.

As noted above, teams that are considering extensions of current players — especially, those close to reaching free agency — can also utilize the threat of a QO (implicit or otherwise) to achieve leverage. That may mean little in negotiations with superstars, but could have a sizeable impact on talks with "merely" above-average players. The possibility of a qualifying offer adds to and even enhances the risks of injury or performance decline already present to an above-average free agent-to-be, which could result in savings to current teams. This factor is, perhaps, enhanced in the situations of older or defensively-limited players who could be looking at short-term contracts after their walk years, even if they put up good numbers.

C. Impact On Players Subject (Or Potentially Subject) To Qualifying Offer

Meanwhile, for players, those issued a QO are subject to the whims of their team and other circumstances outside of their control. The take-it-or-leave-it offer is presented at the team's initiative, before the market even opens. (This year, for instance, Ubaldo Jimenez came with draft compensation; Matt Garza and A.J. Burnett did not.)

Further, the cost of the small reduction in overall spending falls squarely on the shoulders of the small number of players who are made a qualifying offer: their market value is decreased by whatever amount prospective teams choose to discount for the lost pick. And that burden is not shared by any other stake-holders (other players, the league, teams).

One line of sentiment says that some players over-value themselves by rejecting the QO. (No player has yet accepted one.) Even if the offer is an arguably fair price for one year of a certain player's services, however, that does not end the matter. It is quite difficult to reach free agency through service time, let alone to do so at an optimal point in time. Players that do naturally seek to maximize their overall guarantee, often choosing a longer contract with a lower average annual value to avoid the risks inherent in suiting up for another season before securing a future commitment. As Ubaldo Jimenez recently explained it: "I knew that I would have a better offer than the qualifying offer. Or at the very least, I wasn't as much worried about the annual salary, I was more concerned with having the long-term security."

For those that decline the qualifying offer and test the market, the resulting tie to draft compensation can be a significant drain. Though it is often suggested that the downside of the QO system lands solely on the more marginal players that receive an offer, that may be true only in relative terms. We do not know whether, say, Robinson Cano would have garnered a $245MM (rather than a $240MM) guarantee from the Mariners without an offer. But it is likely that the impact of a lost pick was factored in on some level. While the effect is a relative drop in the bucket for top-dollar free agents, it appears nonetheless.

(This is not to suggest that the team would have any focus on the loss of the draft pick in negotiating with a star-level player; rather, the value of the lost pick would be baked into the valuations that the team uses in setting internal parameters before entering negotiations. As Blue Jays GM Alex Anthopoulos has explained, for example, "there's still value" even for picks after the first round, "and you still build that into an offer." Of course, teams may still be willing to go past those valuations to land premier free agents, and/or effectively adjust their internal valuation of a pick downward based on their present roster construction and expected point on the win curve.)

More importantly, though, it is clear that non-superstars take the largest proportional impact. That is made obvious by Nelson Cruz, who recently became the first QO-declining player to sign a deal worth less than the qualifying offer itself, with his one-year, $8MM contract falling over $6MM shy of the $14.1MM he could have taken before the start of free agency. (Previously, the least guaranteed money in a deal to a player who declined a qualifying offer was Adam LaRoche, who signed for two years and $24MM last year after declining the one-year, $13.3MM QO.)

Indeed, the greatest risk for a player may lie not in the possibility that they will see a reduction in their earnings to compensate for the value of a lost pick, but in the impact on that player's overall market. Some teams may decide that they will not sacrifice their draft pick in a given year at all, for any number of reasons. Others may decide that, whatever the theoretical value of the pick, organizational needs dictate that they not cede the choice unless they are signing a player of a certain, higher order. Some clubs may simply put a greater internal value on the draft choice than that suggested by Cameron.

Whatever the case, teams clearly do not take lost picks lightly. "You hear people say, 'Well, what if the [drafted] player doesn't make it,'" Brewers GM Dough Melvin has said. "That's not the sole purpose of a draft pick. You can use those picks for trades. … I'm glad we have Kyle [Lohse], but don't tell me that about overrated draft picks. Their asset value is huge." The net effect, in all likelihood, is often to take away some teams that would be potential suitors and, perhaps, to limit the willingness of some others to offer multiple years.

This could explain, in part, how a player like Ervin Santana ended up taking a one-year pact (at the precise value of the qualifying offer) just to get in camp before the end of the spring. This kind of situation is not unprecedented even without draft pick implications — for instance, Edwin Jackson signed a $11MM pillow contract with the Nationals the year before the QO system went into effect, and did not cost the Nats a pick (he was a Type B free agent under the old system). Like Jackson, Santana had multi-year offers, apparently at about the price achieved last year by Kyle Lohse. But Santana was unwilling to sign for three years at a total value roughly equivalent to two years of qualifying offers, as was Lohse, and was apparently unable to translate relatively strong demand into a fourth year.

The point here is not that the QO in and of itself prevented Santana from achieving the four or five-year deal he was hypothetically entitled to. Rather, it is that, for the reasons just noted above, the qualifying offer played a role in dampening his market and reducing his leverage to pry away more years at a strong average annual value. And that, in turn, makes for an even greater potential increase in the proportion of the burden borne by a limited class of players.

Then, there are the soon-to-be free agents facing the possibility of a market hampered by the burden of draft compensation. As noted above, their leverage is surely reduced by the prospect of carrying that added cost, especially if always-shifting demand turns out to be less than robust. And the qualifying offer introduces risk to the player through the unpredictability of its effects, especially since the system drastically skews the market (through the protection of some draft picks and the fact that teams signing multiple compensation free agents sacrifice increasingly less valuable choices.) Indeed, players like Justin Masterson and Chase Headley have reportedly seen their current teams insert the qualifying offer into extension talks.

D. Conclusion

With this understanding of the broad parameters of the function of the qualifying offer system, the question becomes one of purposes. What does the system hope to accomplish, and hope to avoid? And how well has it done? I will suggest an approach to those questions in a second post.

Morales and Cruz would not have gotten anywhere near $14M aav though without the offer. If you take a pretty optimistic WAR projection for Morales and stick $6M per WAR, it pops out $9MM salary, which I think is a lot closer to what I think he is worth on the market. Cruz is maybe worth $11MM, both on short term deals. They both overvalued their markets IMO. March can be a tough time to get a big contract, just because teams already have their teams set, and have convinced themselves enough that things will work out. Red Sox have warmed up to the fact of Bogaerts, and DH is even harder for Morales, just because so many players can fill that position. At least Drew has position scarcity, Morales and Drew don’t, which makes the fact of their only average offense hard to get the contract.

Morales and Cruz probably could have reasonably hoped for something like that AAV on a shorter deal, with the idea of settling for slightly less (a la LaRoche) if things didn’t work out. WAR is a useful stat, but not the end-all, especially when market forces intervene and where players like these are involved. They are both somewhat niche players who have more value to certain (mostly AL) teams with certain needs … which also limits their market, as you note.

Right, was just trying to see what WAR would give me. FG has done a few good pieces this week showing there is a pretty strong correlation between War and contract value. Both players are basically just outside of the top 50 batters in baseball, and they have little to no defensive value. Being a DH is hard, unless your Ortiz or Butler. You limit yourself to 15 clubs, and a large portion of those teams figure to rotate.

Yeah, I saw Cameron’s stuff. Definitely interesting. I probably like WAR more than most people who are not pure quantitative types, but I suspect it is much less useful (both in general and as a contract-predicting tool) for certain types of players. Obviously, relievers is one. Could be that defensively-limited sluggers is another, since some teams will be able to make better use of them then others (e.g., having two stellar defensive outfielders to pair with Cruz, or an open DH slot, or a useful platoon situation where Morales can take just 1/3 of the ABs at first.)

But yes, 100% agree that the resulting market is narrower and more variable. That is precisely why the QO hurts these guys so much. It’s easy to say in retrospect that they should have taken it, but they had to decide whether to do that or roll the dice on what could be their one shot at a long-term contract. Hard to fault them for trying, and I am not sure they should face that near-impossible decision.

I think next year you will see less players like Cruz or Drew being offered QOs because more players like them will accept the offers. Royals are probably happy that Santana rejected them and I doubt Atlanta makes the offer next year. The market will sort things out.

Good piece! My biggest issue with the QO system is not that it harms players’ earnings, 14+ MM a year is a fine salary, but that it unfairly benefits large market teams. Large market teams like Yankees, Red Sox and Dodgers can afford to make QO’s to far more players than small market teams, for example the Pirates. The Pirate couldn’t risk spending 14 MM on 1 year of AJ Burnett but the Red Sox are perfectly happy to risk a player like Drew accepting a 1/14 deal.

The non superstars have had inflated salaries relative to their production for far too long. The Pirates made a mistake not tendering a QO to Burnett. They could have afforded taking that chance on a one year deal because they could have traded Burnett halfway into the season.

As I stated above I have no issue with the QO system decreasing salaries for non-star players but to teams like Pittsburg or the Rays there is far more risk involved in offer a player a 1/14 deal than their is for larger market teams. Spending 14 MM a year on a player just doesn’t carry the same risk for large market teams as it is for smaller market teams thus allowing large market club the ability to offer QO to more FA and acquire more draft picks.

I agree with you on this point — it makes an impact on the margins. In large part, it is a problem created by the one-size-fits-all nature of the QO system.

Looking back at how things unfolded, it seems they just pursued a high-risk strategy and m;issed. Seems plausible enough that he’d have accepted, which would have prevented them from pursuing Josh Johnson, who seems to have been the target. By putting their money where their mouth was on the QO being too expensive, they also kept open the possibility of landing Burnett on a much cheaper deal if he really only wanted to play in PIT.

Thanks. I will take a look at some of these issues further in another piece. I would note that, while $14 mil a year is undeniably a “fine salary,” that doesn’t mean it is a market salary — especially on a one-year term. My biggest problem with it is that it falls so disproportionately on such a small number of players.

I don’t think Burnett is a fair example given his “Pirates or retire” sayings and the fact that the Yankees had been paying a bulk of his salary.

The Yankees and the Red Sox are benefiting from this right now because they’re the ones with big money players hitting the market. We’ll see more of the smaller market teams involved once their younger players who signed extensions early on hit the open market.

Fair point regarding AJ but take the case of Bartolo Colon and Hiroki Kuroda. Both put up very similar numbers, Colon 3.9 fWAR age 40 Kuroda 3.8 fWAR age 38. Kuroda was offer a QO by the Yankees, Colon was not offered one by the A’s. Not a perfect comparison but it does eliminate the “Pirates or Retire” element

Kuroda made 15 million last year. Colon made 6 after his incentives were met. So you’ve eliminated the “Pirates or Retire” element, but citing Colon’s numbers doesn’t take away from the A’s reasonable reluctance to give him an 8 million dollar raise.

That is precisely my point. NYY wouldn’t bat an eye at giving a player a substantial raise like that. NYY gave Kuroda a 5 MM dollar raise in 2013 no problem, Boston offered Drew 4.5 MM raise but to teams like the A’s and Pirates giving players a major raise is just not an option.

The Yankees did let Colon go once over what seems to be no problem to you.

The problem with Kuroda and Drew is that they were both wanted back by their teams. Did the A’s really want Colon back? I’m not sure the answer to that is yes.

If Boston wanted Drew back why is he still a FA?

I used the past tense for a reason. I don’t think they want him back anymore now that both Sizemore and Middlebrooks are exceeding expectations, but Drew had plenty of opportunities to go back that Boras likely botched.

Fair point regarding AJ but take the case of Bartolo Colon and Hiroki Kuroda. Both put up very similar numbers, Colon 3.9 fWAR age 40 Kuroda 3.8 fWAR age 38. Kuroda was offer a QO by the Yankees, Colon was not offered one by the A’s. Not a perfect comparison but it does eliminate the “Pirates or Retire” element

What makes Pittsburgh a “small market” and Boston a “large market”. Population: Pitts: 20th, Boston 21st, Pittsburgh has 7 Fortune 500, Boston has 2.

Pittsburgh isn’t hurting in football or hockey. Yet, you include Boston with NY and LA, the two largest cities in the country. How about Pittsburgh is a football town, and Boston is a baseball town.

Boston’s 2013 team payroll: 153 MM

Pittsburg 2013 team payroll: 66 MM

Team spending not population determines large v small market teams. Pittsburgh may be a rich city but the Pirates are not a rich MLB team.

That means LAs market has blown up from 95 mil to 221mil in 4 years. Don’t think so.

I disagree with this, as it conflates cause and effect.

imo, revenue is what determines small market vs. large market, not payroll. Would you consider the Mets, who play in maybe the biggest market in all of sports, a small or even mid-market team? Their payroll is b/t $80-90MM, so by your standard they would be. Even as a fan of theirs, I’d say they’re large market, based on revenues/tv money/etc.

Boston metro area has a GDP two or three times larger than that of Pittsburgh’s. And many of the markets ahead of Boston by this measure (NYC, Chicago, LA, Bay Area) support two clubs. This is what makes Boston a “large-market club,” thanks for asking.

“3 times larger” no way. But, you make a legit point.

People who live in suburbs don’t watch baseball?

Boston is the 10th largest metro area, with a population of 4,591,112

Pittsburgh is 23rd, with 2,359,746. Boston’s market is almost double that of Pittsburgh.

Bostons market includes most of NE. Pittsburgh has a lot of competition nearby in geographical terms,

I like the QO system. One of the biggest problems in baseball has been the overpayment to “non superstar” players once they hit free agency years. The reason this happens is that only the top 8-10 franchises can realistically bid in the open market for actual superstar players. This is a structural problem in a sport that unlike the NFL doesn’t equally share media revenue.

As a result the good, but “non superstar” players have had contracts inflated over the years by having more teams vying for their services than the actual stars of the game as many of these teams are completely shut out of the superstar market. That actually deepens the talent gap between haves and havenots because the fail rate for the lesser players is higher and low revenue teams get stuck with bad contracts more often.

It’s theoretically a better game when there aren’t players who no longer play to acceptable standards taking up roster spots solely because of the amounts remaining on their deals signed years earlier. In the NFL if a player can no longer play, he’s gone, presumably replaced by a player who can play. That makes for a better product on the field. Now baseball will likely never revert to non guaranteed deals, but the QO system at least attempts to reign in spending on guys who’s impact on the game was not all that strong to begin with.

I found this interesting, and I’m trying to think through it. So, these are more thoughts than developed arguments.

First thought: lots of differences with NFL, where drafted players have an immediate impact on the field, the shelf life of most players is shorter, much less guaranteed money is tossed around, and there is a hard salary cap. Those factors may have an equal or greater role than revenue sharing in the differences in bidding for superstars.

I’m not sure I agree with the premise that lower revenue teams have been stuck with more bad contracts than higher revenue clubs. Here are some non-mega deals (~$25-75MM) of recent vintage that aren’t looking too hot or didn’t work out for one reason or another: BJ Upton (Braves), Heath Bell (Marlins), Jonathan Papelbon (Phillies), Adam Dunn (White Sox), Jason Bay (Mets), Chone Figgins (Mariners), Derek Lowe (Braves), Francisco Rodriguez (Mets), Oliver Perez (Mets), Milton Bradley (Cubs). Anything less than 25 mil over a few years, and it’s hard to say any team would really be hamstrung by a contract. Random sampling, to be sure, but most of these deals are from mid-to-top-tier payroll clubs. There are other deals you could probably name as examples on the other side, but the clubs that ended up stuck with these really bad mid-tier contracts were not the lowest payroll outfits.

On your last point, I think teams are generally savvy enough to understand that it is not worth keeping a guy just because he’s owed money. The money has already been committed. There are plenty of examples of players who are completely cut loose or are dumped while eating most of the salary.

Finally, I wonder if your last point doesn’t go the other way. If it’s true that mid- and low-payroll clubs can only compete for flawed, non-star players, then is it preferable to force them to give up draft picks to sign them? They may end up both overpaying and losing future value. Or, perhaps, they’ll bow out of such players and let larger-market clubs have them. After all, the QO system doesn’t benefit signing teams, it just impacts what they have to give up to get the player (future value rather than present cash, at the player’s expense).

There is absolutely nothing wrong with the QO system that a simple tweak won’t fix. It is absolutely senseless to penalize a team for signing a free agent merely because he declined a QO. If a QO was not made to that same free agent for whatever reason, there would be no penalty. The signing team has nothing to do with whether the FA’s prior team does or does not make a QO. I can understand the logic of compensating the team losing the FA after they have made him a QO. That team sould receive a supplemental draft pick in a supplemental round between the first and second rounds. If they lose a second QO FA, they should get a pick in a second supplemental round between rounds 2 & 3, and so on. The picking sequence in the supplemental rounds should be the same as the original selection sequence. The signing team should, in no way, be penalized.

I agree 100% with your point on separating the forfeiture from the compensation aspect, as you’ll see when I post the next piece (creatively titled, “assessing” the QO sytem). I think there are still arguments to be made for requiring signing teams to give up picks, but it creates illogical results when, e.g., you can sign Garza without giving up a pick but have to burn one for Jimenez.

What is the rationale, or dare I say the net market benefit, to requiring teams to give up first round picks for signing a free agent player? I don’t see a good one, other than an attempt (which I think is failing) to limit the hoarding of free agent players by the wealthiest clubs.

The previous CBA actually had a flat limit on the number of Type A and B free agents that a club could sign. The limit was reached only once, when the Yankees signed Sabathia, Teixeira, and one more. But they were also allowed to sign another to replace Matsui, who left for Anaheim. It wasn’t really much of a limit.

The only real impact remaining, IMO, is the suppression of salaries, or limitation of the movement of certain players because clubs don’t want to give up a first round pick to sign them. To me, that is not a desired effect.

The argument on the forfeiture side, essentially, is that you might want teams that prefer to acquire present production (through mid-career players that reach free agency) to be required to sacrifice future value to do so, rather than just spending present-day cash. If you lose enough picks and bonus slots, you will pay the piper ultimately. Scarcity (both on the supply and demand side) could otherwise allow some clubs with very high revenues to spend their way to championships in a way that isn’t really possible under the present system. (As others have shown, spending correlates to winning, but hardly does so perfectly. The game has pretty good competitive balance overall.)

At base, this relates to the distinction between real-world and baseball-world resources. The overall business imbalance between the Yankees and Rays, say, is vast, and would surely create unsustainable imbalance in the long run in a totally unregulated market.

I see the concept of deterrent, but taking your example of the Yankees and Rays, it does not seem that the current system has deterred the Yankees from signing free agents at all.

In fact, the system makes it less costly for a team that has already signed a QO’d free agent, than it is for one that can not afford to do so. The system benefits the wealthier clubs in two ways in this regard. First, each QO free agent signed costs less than the last as they move down the draft board. Second, it is those clubs who have been receiving the compensation picks and they use those picks as payment of compensation to sign more QO free agents.

What the system has created is a relatively modest recycling of these low first round to supplemental round picks. (The higher supplemental picks are now in the place of what would be low first rounders.)

There is a rational basis for limiting the hoarding of free agents and limiting unchecked spending. I think that the luxury tax does a better job of that than the QO system, and the next CBA will eliminate the luxury tax.

I am not saying it’s a perfect deterrent, and in fact think that aspect should be beefed up. I was just referring to that as a possible goal of the system.

I agree that high-revenue clubs can take advantage of signing multiple comp FAs, as I mentioned elsewhere in the comments. (However, the fact that teams gain and then lose comp picks tends to increase the cost to them — they lose less volume of picks, but the comp picks are much more valuable than 2nd, 3rd, etc round choices.)

I’m sorry, Jeff, but I don’t see your point on scarcity. It is clear to me that under the current system, ultra-high revenue teams (again, e.g. Yanks, Dodgers) try to spend their way to a championship, precisely because of the correlation between spending and winning, despite the imperfection of the rule.

I think we all agree that a totally unregulated market is untenable. The solution is in the redistribution of excess revenues through the luxury tax, but where the penalty monies collected from teams with payroll spending in excess of the limit, (currently $189 million, I believe) mandated to be spent, in its entirety, by each receiving team, to increase their payroll in a like amount beyond their prior year’s payroll.

I was probably unclear in trying to respond to a lot of comments, but my point on scarcity is something like this: there are relatively few elite options (on all markets: free agent, draft, international, extension, etc). There are relatively more good, and relatively even more average, and relatively lots of replacement level options. If teams are allowed to throw money in an unrestricted manner at each of the markets, the quality of players will simply align with money (elite, good, average, replacement).

It is arguable, then, that the rules should force a team signing a high-end free agent not only to give up a lot of cash — which high-revenue teams may have more of than they can even spend due to player scarcity — but also to give up significant future value.

Obviously, money matters and teams try to spend their way to championships. I don’t dispute that at all. And tax and redistribution is one method to encourage competition. But there are other methods to help make it so that more spending loses out, at least sometimes, to smart spending (including $ on scouting, development, etc).

Your tweak would be a boon for big market team and big spending. The exact thing the QO system is trying to slow down. It would create a huge disparity for teams that can’t afford to offer QO’s or sign top FAs.

Big market teams would out bid for the best FAs and, also, have a stacked minor league system. The current QO system is trying to say “one or the other”.

No! Actually, it is a boon to small market teams who desperately need the draft to continually build their teams. Big market teams (Yanks, Dodgers) spend like water under any system, make the QOs to their departing big ticket FAs, and thus often recoup the draft picks they lose in signing high priced FAs. They are indiferent to the draft, relying primarily on the FA market to build their rosters. It’s the small market teams that have to think long and hard as to whether to extend their budgets to sign an elite free agent at the cost of a precious draft pick.

You must realize that the big market teams almost always out bid smaller market teams under the current system, except when the smaller market team is willing to seriously overpay. (e.g. Cano to Seattle) Or are you a Yankee fan?

A big problem in baseball are “dead money” contracts. The QO system at least is an attempt to reduce that impact. The Cubs being pitiful for 3-4 years and basically not even trying to compete for that long is not good for the game. The need to rebuild them from the ground up was essentially the result of them being buried by dead money for deals negotiated by the Hendry regime and while they are “big market” in a sense they are limited by owners heavily in debt, and a park that doesn’t generate much revenue.

I’m not sure how the QO system really does this. For one, a rebuilding team like the Cubs doesn’t really benefit from it, because they don’t have any players who are worthy of a QO (at least until Samardzija hits the market, thought that would be a poor return of value on him). For another, the major impact (from a relative perspective) is not on the truly large contracts (e.g., looking back, the Alfonso Soriano deal for the Cubs). It is on the more marginal guys, like Cruz/Morales. Finally, baseball teams are sophisticated entities that can make market assessments on their own. The experience of the Cubs is a good lesson for that franchise and others.

As for the point about market size, one thing I believe is that the notion of large-market teams benefitting is not really true … in some respects. The teams reaping draft picks aren’t necessarily larger markets, they are for the most part good teams. This makes sense, since good teams not only have good players, but don’t trade them in mid-season. (On the other hand, high-revenue clubs have potential advantages in making QOs to more marginal players and have greater capacity to sign multiple compensation FAs in one offseason, reducing the forfeiture of draft picks on the other end.)

But, with no salary cap, the larger market teams have a much better chance of being the “good teams”. If most of the teams reaping the picks are the teams that aren’t mid-season sellers, the chances of such teams being from a larger market is much greater. Or at least, the path to become one of the teams who is in a position to take advantage of the QO system is much simpler for a club who spends money in the offseason and at the deadline. To me, that means the goal of the QO offer system is failing. There’s a reason the Yankees are never considered “sellers”. There’s also a reason the Yankees had 3 picks 2 years ago and the Red Sox had 3 last year.

What teams are losing star players that aren’t being compensated? The smaller market teams played it smart and signed their younger players to extensions.

That’s not the point. The point is the signing of such players. It’s easier for teams with big budgets to sign players that will eventually be QO players. It’s also easier for teams with big budgets to hedge the impact of losing draft picks with payroll, hence making it easier for big market teams to sign the QO players. Also, it is easier for teams with big budgets to hold onto players past the trade deadline so they will qualify for QO. Almost every facet of the system benefits large market teams….like I said…proof is in the pudding…Yankees and Red Sox killing comp picks the last 2 years

I wouldn’t say the Red Sox are “killing comp picks.” They’ve resigned 2 of the 4. The sample size is also unfair since 3 came from this year. The Yankees will always be outliers because they are the Yankees.

I also wouldn’t say that teams with big payrolls sign players that will eventually be QO players. What does that even mean? Will Ellsbury or Beltran get another QO?

No, the players that get the long term deals don’t get impacted by future QO ramifications. But the players that are stuck in the year-to-year limbo of QO will again be hurt. And it’s still easier for the big market teams to sign those players. Small market teams just aren’t going after middle-tier QO players. It’s just not happening. That’s a large reason why the Twins ended up with Nolasco as opposed to some of the other pitchers that had pick compensation tied.

And true, the sample size is small, but the way this system is trending it’s only going to skew further. We’re in for a big snowball effect.

Pirates couldn’t afford to give Burnett the offer, even though it was a discount on his market value. They were uncompensated.

They were still “in” on Burnett even after they signed Volquez. I don’t buy the idea that they couldn’t afford him. They may not have wanted a 14.1 million dollar Burnett, but they had their chance and they chose not to.

What teams are losing star players that aren’t being compensated? The smaller market teams played it smart and signed their younger players to extensions.

Jeff, I think the point about better teams gaining the comp picks isn’t that those clubs get a net benefit, but more the fact that the non playoff teams DON’T benefit from the QO system. Much of that is because they either extend their potential free agent players or trade them, rather than lose them for only a supplemental first round comp pick.

When you remove the perceived “benefit” of non playoff teams gaining compensation picks for losing players, what remains is the artificial suppression of that segment of the free agent market.

I think it’s fair to say at this point that the MLBPA underestimated the impact of the QO system on that segment of the free agent market, and that is understandable. Teams are much more reluctant to part with a first round pick than they were under the previous CBA, when the QO was essentially an offer of arbitration.

One thing not mentioned is the incentive for a player to remain with his current club. I don’t think that there is a usable metric to put a dollar value but I think there is long term revenue value there for the clubs to keep their fans watching games live or at home.

Yes, this is probably true. As I think someone rightly mentioned in the comments of my Giants review post, Lincecum’s contract is a good example of this.

The question, though, is whether or not the system actually accomplishes this, which is one of the things I’ll touch on in the next round.

I actually like this system, it forces more players to entertain extensions with their current teams rather than allowing a pure free market for the bigger spenders to spend on all the premium talent and inflate the market. This allows smaller market teams to better compete on the field and help keep their star players in town, at a fair value, to sell more tickets for longer. Stars spread throughout more teams is better for the game rather than having a few teams with all the stars.

It can create some extension pressure, which of course ultimately is not to the benefit of the player but may well be good for the game. That’s okay as a general matter — the whole CBA has benefits and drawbacks throughout, to both sides — but I still wonder if there are better ways to accomplish that. Even a very good, non-superstar player like a Justin Masterson could (if he wanted, which apparently he does not) simply say: “go ahead, make me a QO, I’ll still probably get a bigger multi-year offer from a large-market team.” Meanwhile, the draft compensation is too low to transfer leverage over true stars.

When looking at the impact on the overall market, one has to consider WHO is receiving compensation picks. So far, every team that has received a comp pick has been in the playoffs at least one of the past two years. The Yankees have received- and given up- more comp picks than any other team. Obviously, it’s the teams who sign high priced free agents that also pay the compensation, so they’re just moving late first round and second round picks around the board.

If the objective of the system is to suppress free agency somewhat, it’s having that impact. If the objective is to compensate teams who can not afford to extend the players that they’ve developed when they leave, it hasn’t had that impact so far in the two years under the current CBA.

I’ll address that in the next post, but generally, as I noted somewhere else in these comments, it isn’t surprising that teams with winning records are the ones making the QOs. Garza and Greinke would have received QOs, but were dealt mid-season instead. Note that the Yankees are also looking to be just about out of QO-worthy players who will hit the market in the coming seasons.

Of course there are ways in which it can be done but the Players Association will never agree to a salary cap and the owners will never agreee to complete revenue sharing like the NFL. Thats truly the only way to ensure teams can only spend so much on free agents and keep competitive balance. Players benefit more from a completely free market and teams that make more than other teams can pay more for their services. True competitive balance only works if every team has the same amount of money available to them to spend otherwise teams with more money can spend more and teams with less money will spend less and the players will almost always choose the team with more money because its in their best interest.

It helps mid-market teams but the benefit for the smallest market teams is practically negligible. When they do get these quality talents and they do end up heading toward Free Agency, the teams at the bottom still need to entertain moving them in a trade for a greater prospect return than one draft pick. So this system is meant to reward a small-market team that develops a player and holds onto them until Free Agency- but mostly you get a team like New York or Boston that are extending offers to players they’ve previously acquired (or maintained control of) through FA. Boston got Napoli and Drew on one-year deals just last year.

It seems to me the system is actually much more beneficial to large-market teams that are picking up quality veterans on one and two-year contracts, as they can then attempt to either retain their services at a market discount or get draft pick compensation for their departure. It would be interesting to see the varying types of players that get Qualifying Offers, on the range from BJ Upton or Michael Bourn (organizational fixture) to Stephen Drew or Shin-Soo Choo (recent acquisition)

All teams need to entertain moving players heading toward free agency for a greater prospect return than one draft pick. The level of return isn’t up to them.

All teams make this calculation but it’s Tampa Bay, Pittsburgh and so on that most heavily rely on return from developed players for organizational health. For sake of keeping their clubs competitive and cost-effective they often need to get more than a supplemental round draft pick for a player they’ve developed. This is why everybody was so shocked when the Rays actually held onto Price.

Tampa Bay has frequently let players go in free agency to get picks.

B.J. Upton, Carl Crawford, Carlos Pena, and Rafael Soriano got them nice draft picks. They might have traded Kazmir, Shields, and Garza, but citing them to prove your point does not really work.

Pittsburgh uses the draft and extension strategy. McCutchen is a great example of this. They haven’t had to extend anyone else yet, but will as more of their youngsters start reaching arbitration. The Pirates make money anyone saying they can’t afford to pay their players more is lying.

I think after this years fiasco with players taking equal or less money as the QO, many players will realistically look at if they deserve more money. Like said in the article, many players over valuate themselves. I wonder if an agent will tell someone in the future that they probably won’t get more money on the open market.

I think after this years fiasco with players taking equal or less money as the QO, many players will realistically look at if they deserve more money. Like said in the article, many players over valuate themselves. I wonder if an agent will tell someone in the future that they probably won’t get more money on the open market.

Players still want, and deserve the opportunity to sign multi year deals.

Sure, but they could still sign a multi year extension with their current club.

Depends on which situation, and either way, forcing a player to narrow his market from 30 teams to 1 team gives the club a monopoly on the salary of that player.

I don’t think the Red Sox were interested in signing Drew to a long-term deal, if not at a severely discounted price. They didn’t want to block Boegarts, so Drew should have a fair shot to test the open market. His pick compensation then killed his market. He was in a lose-lose unless he wanted to sign the QO. But then again, doesn’t he deserve the opportunity to not play year-to-year?

The QO doesn’t create enough consequences for teams that offer it. They can essentially offer it, knowing that the player will decline and then not negotiate in good faith. Free agents want years of security. Teams need to be obligated to more than one year/14.1 million if they’re going to make that offer.

Interesting idea….how about a tiered QO system based on contract length? For example:

1 year QO $14 mil- 3rd rnd pick compensation

2 year 27 mil- 2nd rnd pick compensation

3 year 40 mil-1st rnd pick compensation

this is the direction my mind is headed, fwiw

There isn’t a risk to the offering team? The Red Sox were a simple “yes” away from making Stephen Drew the 5th highest paid SS in baseball. His career OPS+ is 98, and he managed a 110 last year, his first time above the league average since his age 27 season.

Drew is not an All-Star, he’s never lead the league in any category (or even really entered such a discussion) and he’s not likely to become a different player at age 31 than he has been his entire career. But we’re supposed to think he’s entitled not only to a $14M offer, but multiple years?

With League Average upside for Drew, why wouldn’t a team take a shot with a much younger SS with long term control.

Also, with so much talk about long-term security, we should also realize, had Drew accepted the Red Sox offer, his career earnings after the 2014 season would have neared $45M. This is not a guy who’s been making league minimum his entire career and is by no means hurting financially (at least has no reason to be).

Of the 13 players who were offered a Qualifying Offer, Only Cruz could make an argument that he had missed out on a opportunity previously not available to him. Many had signed extensions of some sort during their career or had used the arbitration system to find significant paydays. Others were fully capable of cashing in on their new opportunities and signed deals that would provide security to anyone.

Morales, Drew and Lohse are the poster children for the evils of this Qualifying Offer system, but the truth is, they are/were players with questions and the big payday wasn’t going to be there regardless. Morales is a guy who was never the same since breaking his leg and is essentially a DH only. Lohse already signed that big deal when he got 4 yrs and $40M from the Cardinals. At 34, he wasn’t going to get a 5 year deal, not for a guy who’s never been an All-Star nor really been a Cy Young candidate. Drew I already discussed earlier.

So who’s the Stephen Drew of 2014? JJ Hardy seems to be lined up for a similar off-season. The Orioles haven’t reached out to him for a long-term deal and Machado is going to play SS at some point. A multi-year deal is likely for defensively gifted SS with serious pop in his bat, but will the QO of more than $14M be too much to pass up considering he’s coming off a $7M 2014 salary? Are the Orioles prepared to pay him that money for one more year when their preference might be for him to simply go away. The Giants may be painted into a similar corner with Pablo Sandoval.

I think there’s plenty of risk to go around, Drew and Morales just made poor decisions and their agents should be the ones taking the brunt of the criticism.

I’m not sure if this is directed at a specific thing I said or just a general comment about my not including that risk to the team, but I take it to be the latter.

I agree there is risk in signing the player, if they take the offer, just like any other signing. I suppose I could have mentioned that. But there is no strategic risk through the existence of the system, because the team can simply bake the player risk into its analysis like it would w/r/t any other signing decision. That risk isn’t driven by the system, in other words.

When valuing Drew, or any other possible QO recipient, the team just assesses his benefits and drawbacks against team need to arrive at his value. The team can continue to do that as normal under the QO system, and decide whether to make the offer (after assessing the QO situation – will he accept, what happens if not, etc).

The player, on the other hand, is subject to their prior team’s whims, and then the whims of a shifting market. Their only agency is in deciding whether to take a set-price, one-year offer when they have yet to have the opportunity to test the market fully.

this is the direction my mind is headed, fwiw

One change needed is teams who acquire a player part way through a season are not entitled to any compensation when/if that player walks at the end of the year. When you trade multiple good prospects for a player, and that player walks you deserve some compensation for the player leaving. You should be able to make a QO to a player and gain some draft compensation.

Jeff – what about this tweak? Expand the QO to be a choice – more money but shorter term (say, 1/14 as is the case this year) or less money and longer term (say, 2/10 per year)? Leave it to the player to decide whether he prefers more money, more security, or take his chances in the open market. In other words, the QO itself doesn’t have to be a single option.

Agree with the instinct … I’m still thinking about how to suggest a workable system that draws from it, but will probably give it a shot!

Jeff-It seems that the QO system has stratified the players that sign as free agents into their comparative team level. By that I mean, the middle tier QO guys (Santana, Cruz, Jiminez, Lohse) are going to middle market teams after the cream of the crop guys (Cano and Choo) end up going to the bigger market teams without much regard to the comp pick. All in all, the small market teams seem to be completely out of the equation. I don’t really know that I’m trying to say that there needs to be a system in play that “forces” small market teams to be involved in free agency, but it seems like the current system isn’t much different and may even be worse for parity than the old system. Do you agree?

Small market teams get revenue sharing dollars. Many of them spend far less than the MLB average of 47% payroll/revenue, as low as 15% in some extreme cases . Limit teams ability to collect revenue sharing dollars to those teams who spend 40% of revenue (including revenue sharing dollars) on payroll. So if the Marlins have a payroll commitment that would be only 20% of payroll with revenue sharing dollars, they can kiss that 30 million dollars in revenue sharing dollars goodbye.

Another idea is to take all the revenue sharing dollars and distribute it small market teams based on performance and not revenue. Give them an incentive to win because right now there does not seem to be much of an incentive. Teams are content to watch valuations and TV revenues go up and pocket revenue sharing dollars w/o much care of ticket revenues. They can get taxpayers to build them new stadiums and they have a legal monopoly where their market is protected from competition.

Don’t forget Cano! I get your point, but I don’t know that ‘stratification’ results entirely from the QO system. The A’s were never going to land top-dollar stars regardless. Smaller market teams are out of the equation somewhat, but I think that’s because they don’t let their best players reach free agency; for the most part, they either extend them early or sell them beforehand. (The Rays did both with James Shields … what incredible value they got out of him on the whole.)

I’m not sure we want to force small-market teams to be involved in free agency. And it would be very premature to speculate on whether the QO system has real overall impacts on parity. (Look at the list of 2015 FAs … looks likely that the big-market dominance could change next year.) But I don’t think the current system is doing what it could/should.

I’d like to suggest a alternate argument. I’d put an end to the loss of draft picks and slot money. I would argue that the more draft picks and slot money you take from the high revenue teams, the less likely it is that they will be able to draft and develop the cheap younger talent that allows them to not splurge in the FA market to fill every position. And the “protected pick” idea in some respects makes it worse, because each year there are high revenue teams who have a poor season, and end up with a protected pick that they can use as a bidding tool. I think we are focused on driving down the price of a handful of players, without acknowledging the impact on the rest.

I find the protected pick to be an arbitrary line, much like the value of the QO itself.

Isn’t the value of the QO an average of AAV’s of the top 100 or so players? Using last year’s numbers, none of the three hitters (Drew, Morales, Cruz) were in the top 100 by fWAR over the span of their careers, and considering that there were only 81 qualified SP’s, Santana for his career ranks right around 54 when compared to other SP’s from last year. And #54? Scott Feldman who got a 3/30 contract, which is what Santana should have been expecting after receiving his QO last year.

Believe it is top 125 players. I don’t mean it’s arbitrary in that it is random or indeterminate, but that there is no particular reason to take the number from that measure as against any other. And, especially, that it is not truly market-driven.

Yes, but those four don’t even deserve that kind of money since 1 fWAR ~$6m, paying them $14.1m is paying for 2.3 fWAR, a production level that none of them have been able to steadily maintain. Now, on a one year contract it’s justifiable, but there’s no real value to be gained for the teams. So this ‘arbitrary’ figure is still a value for the players.

That’s up to the team to assess. And you aren’t allowing for the fact that they are limited to saying yay or nay to a one-year deal, when any player fortunate enough to reach FA with the production and health necessary for a multi-year deal would generally be wise to cash in when they can.

The point is, it creates a non-market-based intrusion that skews not only the individual player’s situation but also the ultimate result of where the player lands (and what it costs his current/former team). I’m not arguing about individual players’ situations and whether they were/weren’t worth the one-year QO price tag.

Anyhow, this post did not pass judgment on the system. I just tried to put it in its full context. My 2nd piece on the topic (“assessing” the QO system) is probably still caught up in our transition process, but has my arguments on the system’s effects.

I think the protected pick should be for every team that doesn’t make the playoffs.

Why should a player be taxed as a free agent after they have paid a hefty tax by playing 6 years at below market value already?

Nobody really argues with compensation, which is giving a team losing the player a compensation pick. Its the tax, which is loss of slot money and pick on the team that signs the player which is the problem,

Why this is a problem now and not as much when teams lost a pick signing a Type A free agent (except for lower paid RP’ers) is an interesting question. It could be teams have independently arrived at the same time on a higher valuation for the pick, or this could be slick attempt by a habitual offender at a limited form of collusion using the draft picks as a cover.

Clark should play the collusion card and force the issue before 2016. End the tax as the tax rate (determined by teams arbitrary and self serving valuation of picks) has become too punitive.

The guys hurt the most have been below average performers over the course of their careers. Perhaps the compensation is waking teams up to the fact that these guys don’t deserve 3+ year contracts or mega deals like they were looking for.

Why is this site set back to March 13? Weren’t the past 5 weeks real?

is this real life?

“As Ubaldo Jimenez recently explained it: “I knew that I would have a better offer than the qualifying offer. Or at the very least, I wasn’t as much worried about the annual salary, I was more concerned with having the long-term security.””

I love this quote, but mostly because Ubaldo’s WAR track record (3.76 fWAR per season) shows that he’s worth more than the QO in overall value. Guys like Drew (~1.8 fWAR per season), Cruz (1.65 fWAR per season), Morales (1.8 fWAR per season), and Santana (2.18 fWAR per season) are older, have injury concerns, or have had major inconsistencies in their pasts, these guys have historically played at less than league average (2.0 fWAR) over the course of their careers. So, paying them for one year of 2 fWAR production isn’t exactly unfair and generally speaking offers them a chance to prove that they are better than their histories have shown. I mean the only guy who was above average that was ‘hurt’ by the QO was Santana and he was only barely above average, just because in the past these types would get 3 year offers off the bat doesn’t meant that they should have been getting them, or that they are entitled, as you so eloquently put it, to such deals. The players may want security, but if they haven’t been able to prove that they’re capable of consistent above average performance, then why should they get it?